For most retired Americans, Social Security is more than just a check they'll receive each month. It forms a financial foundation many would struggle to live without.

Every year since 2002, Gallup has conducted a survey that questions retirees' reliance on their Social Security income. Spanning 23 years, between 80% and 90% of retirees (including 88% in April 2024) have consistently noted that Social Security is a "major" or "minor" income source. In other words, making ends meet would be a struggle without this vital program.

Unfortunately, this financial pillar for seniors is struggling, and part of the blame undeniably lies with immigration.

Image source: Getty Images.

Benefit cuts are an estimated eight years away

Over the last 85 years, the Social Security Board of Trustees has released an annual report that intricately details how the program generates income and tracks where those dollars end up. But the most important aspect of the annual Trustees Report is, arguably, the forecast of Social Security's financial health.

The Trustees account for a number of ever-changing factors, including fiscal and monetary policy and demographic shifts, to determine how financially sound the program will be over the "long term," which is defined as the 75 years following the release of a report. Every report since 1985 has cautioned of a long-term funding obligation shortfall.

Before going any further, let's make clear that Social Security is in absolutely no danger of becoming insolvent, going bankrupt, or failing to make payments to eligible beneficiaries. The way Social Security is designed, with the 12.4% payroll tax generating the bulk of its income, ensures it can never become insolvent.

However, it doesn't mean the current payout schedule, including cost-of-living adjustments (COLA), is sustainable over the long term.

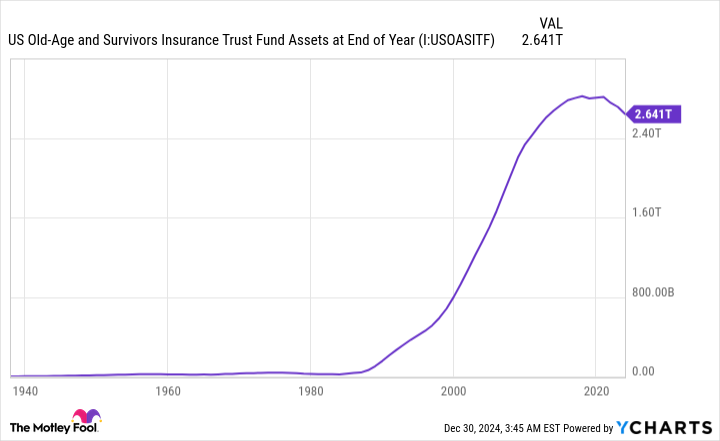

As of the 2024 Trustees Report, Social Security was contending with a $23.2 trillion (and growing) long-term funding obligation shortfall. Even more pressing, the asset reserves for the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund (OASI), which provides monthly payouts to retired workers and survivor beneficiaries, is expected to be depleted by 2033.

Once again, this doesn't mean Social Security is going bankrupt. But based on projections from the Trustees, the exhaustion of the OASI's asset reserves would necessitate sweeping benefit cuts of up to 21% in eight years.

The lion's share of Social Security's woes can be traced to ongoing demographic changes that include rising income inequality, a historically low U.S. birth rate, and immigration.

The OASI's asset reserves are projected to be gone by 2033. US Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund Assets at End of Year data by YCharts.

Social Security's immigration issue has worsened for a quarter of a century

If you were to peruse social media message boards on topics pertaining to Social Security and/or forecasts of impending benefit cuts, you'd pretty much be assured to come across posts that allege immigration -- more specifically, undocumented workers receiving benefits -- is responsible for the program's financial struggles. However, this opinion couldn't be further from the truth.

As noted, Social Security relies on the payroll tax to generate the bulk of its income (more than 91% in 2023). This payroll tax comes from working Americans, which includes legal migrants from other countries.

Most of the legal migrants who enter the U.S. are young, which means they'll spend decades in the labor force positively contributing to Social Security's financial health through work before one day collecting a retired-worker benefit of their own.

Based on the intermediate-model forecast from the Trustees -- the intermediate model is the projection considered likeliest to happen -- net migration into the U.S. needs to average 1,244,000 people per year through 2098 for the unfunded obligation shortfall of $23.2 trillion to not worsen.

The problem is that net migration into the U.S. declined for 25 consecutive years between 1998 and 2023. According to data from the United Nations, the net migration rate tumbled by 58%, from 6.48 per 1,000 population in 1998 to 2.748 per 1,000 population in 2023. Instead of 1,244,000 net legal migrants entering the U.S., only around 958,700 people migrated to the U.S. in 2024, based on the current net migration rate of 2.768 per 1,000 people and an approximate U.S. population of 346.3 million.

Social Security's immigration issue isn't that too many migrants are entering the country -- it's that too few are coming to America.

Image source: Getty Images.

Are undocumented migrants a drain on Social Security?

However, legal migration into the U.S. only tells part of the story. Although undocumented workers often foot the blame for Social Security's woes, data shows they're actually a positive for the program.

If there's a reason that can be pinpointed as to why undocumented workers are blamed for Social Security's crumbling financial foundation, it's the conflation of traditional Social Security benefits and Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which are both run by the Social Security Administration.

Traditional Social Security is funded via the payroll tax on earned income, the taxation of Social Security benefits, and the interest income generated on its asset reserves. Traditional Social Security benefits are paid to retired workers, workers with disabilities, and survivors of deceased workers. Undocumented migrants are ineligible to receive a traditional Social Security benefit.

Meanwhile, SSI is funded by the General Fund and may provide income to asylum seekers. An undocumented worker receiving an SSI check has no bearing on the financial health of the traditional Social Security program.

With the above being said, a 2014 study by New American Economy estimated that undocumented workers generated a $100 billion surplus for Social Security over the prior decade. Even though undocumented workers are ineligible to receive traditional Social Security benefits, they're contributing in the neighborhood of 1% of the annual income collected by the traditional Social Security program.

While undocumented workers aren't a problem for Social Security, a 25-year decline in net legal migration certainly is. Until lawmakers tackle this issue head-on, Social Security's long-term cash shortfall will likely worsen.